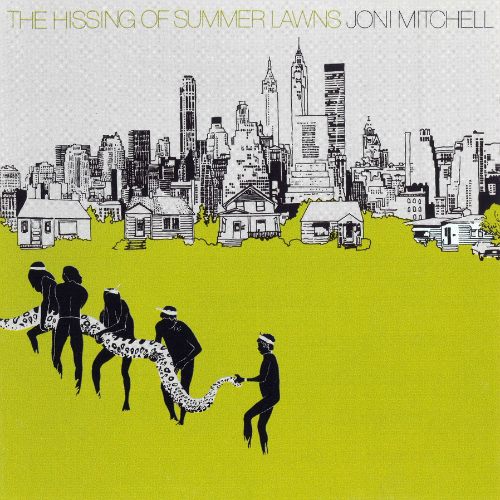

Coming off the commercial success of Court and Spark, Joni Mitchell responds to her newfound fame with a resounding "no thank you." The Hissing of Summer Lawns find her outright rejecting melody and delving deeper into jazz, with arrangements that slink and lyrics that rarely paint a pretty picture. Throughout these ten songs, we meet misogynists, cannibals, addicts, pimps, prostitutes, unhappy housewives and money-fixated businessmen, all before Hissing closes with an anti-hymn. What pops out of the speakers on first listen is "The Jungle Line." Sampling a field recording from the Drummers of Burundi, a centuries-old percussion ensemble from central Africa, Mitchell builds around the beats a fitting ambience to accompany the jungle landscapes of French Post-Impressionist painter Henri Rousseau, for whom the song pays tribute. The downside to a piece like "The Jungle Line" is that initially, everything surrounding it sounds restrained in comparison. But maybe that's not entirely accidental. A recurring theme here is self-imposed suppression, and Mitchell spends much of her time fluctuating between sounding disinterested, displeased or altogether disgusted with the status quo and those that buckle to fit its form. A brazenly feminist record, Hissing is littered with people diminishing themselves down from a person to a concept, wholly preoccupied with presentation: dressed in stolen clothes, mimicking movies, willful prisoners by their own design. Mitchell juxtaposes these superficial facades with the cracks underneath: the runs in the nylons beneath a fancy dress, a priest wearing a pornographic watch, a roomful of Chippendale with nobody to sit in it. And while the characters she condemns are caught up in treating identity as classification, Mitchell herself seems weary of definition: "Nothing is capsulized in me on either side of town. The streets were never really mine. Not mine, these glamour gowns." Judging by this material, Mitchell possesses a palpable anxiety over being boxed in, and she certainly succeeds in making sure that pigeonholing her isn't an option.

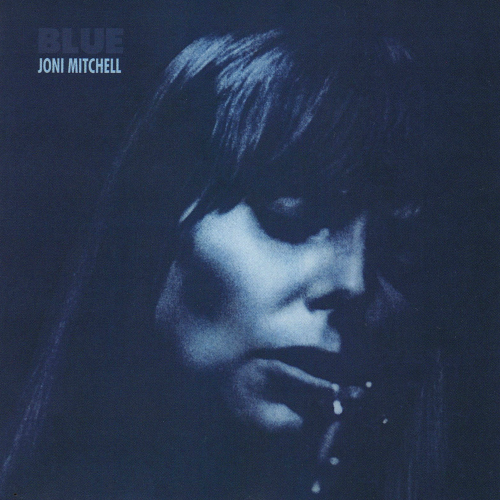

Where previous Joni Mitchell recordings seemed in search of the most poetic way to assemble her words, Blue takes on a more straightforward approach, creating a freewheeling stream of consciousness purging, where perfection or adhering to structure is far less important than just getting the thoughts out. Mitchell's melodically meandering fourth release opens with innocent naiveté on "All I Want" (All I really, really want our love to do is to bring out the best in me and in you) before dissolving into the depths of heartache by album's end. And though the inclusion of Appalachian dulcimer is an effective and welcome addition to the musical palette, it's Mitchell's voice that is the key instrument here, inhabiting and emulating her emotions in a way she had never even hinted at before. Notice how her voice absolutely soars once she hits the word fly on "River," or how the mournful final note of the title track sounds like the musical equivalent of a mid-cry wail. Still, for all the credit Blue receives for being a significant break-up record, it's "Little Green," Mitchell's chronicle of giving her daughter up for adoption, that is the most gut-wrenching of all. Achingly understated, it's all somber resignation before concluding with one progressive, defiant admittance: "You're sad and you're sorry but you're not ashamed." For a record Mitchell indicates was recorded during a period where she felt defenseless, that's powerful.

Page: 1, 2, 3, 4

|